The book, for example, begins, “Welcome. And congratulations. I am delighted that you could make it. Getting here wasn’t easy, I know. In fact, I suspect it was a little tougher than you realize. To begin with, for you to be here now trillions of drifting atoms had somehow to assemble in an intricate and intriguingly obliging manner to create you.” You is one of the most frequent words in the book.

Bryson begins with the Big Bang, discovered in 1965 by scientists wondering about a hiss in the reception from a communications dish, a noise that turned out to be the cosmic background radiation left over from the Big Bang.

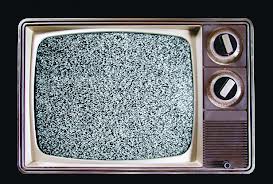

Incidentally, disturbance from cosmic background radiation is something we have all experienced. Tune your television to any channel it doesn’t receive, and about 1 percent of the dancing static you see is accounted for by this ancient remnant of the Big Bang. The next time you complain that there is nothing on, remember that you can always watch the birth of the universe.

Facts brought down to earth, with imagination and humor—that’s Bryson’s signature. Indulge me while I recast this passage to highlight its appeal:

Tune your television to any channel

It doesn’t receive, and

About 1 percent of

The dancing static

You see

Is accounted for

By this ancient remnant

Of the Big Bang.

The next time you complain that

There is nothing

On, remember

That you can always watch

The birth of the universe.

There are 320 million cubic miles of water on Earth and that is all we’re ever going to get. The system is closed: practically speaking, nothing can be added or subtracted. The water you drink has been around doing its job since the Earth was young. By 3.8 billion years ago, the oceans had (at least more or less) achieved their present volume.

Fact and relevance, back and forth: “320 million cubic miles,” “all we’re ever going to get.” Scientists provide the facts; the humanist in Bryson provides the meaning. The message here is not only the environmental nudge but also that our past, the past that created us, is all around us.

I was delighted to see Bryson write at length about the bacteria that were life itself for its first 2 billion years. These eons are usually a tedious blur for those who are curious about evolution and the emergence of flowers, mammals, and humans. I’ve written about this unfamiliar period in Genesis for Non-theists and I can report with assurance that Bryson does it better. Here’s part of his discussion of ancient stomatolites, discovered in 1961, at Shark Bay in Australia:

Today, Shark Bay is a tourist attraction.…Boardwalks have been built out into the bay so that visitors can stroll over the water to get a good look at the stromatolites, quietly respiring just beneath the surface. They are lusterless and gray and look… like very large cow-pats. But it is a curiously giddying moment to find yourself staring at living remnants of Earth as it was 3.5 billion years ago….Sometimes when you look carefully you can see tiny strings of bubbles rising to the surface as they give up their oxygen. In two billion years such tiny exertions raised the level of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere to 20 percent, preparing the way for the next, more complex chapter in life’s history.

The next step was the formation of cells that enclosed nuclei and lived on oxygen; they were bigger and more complex than their predecessors, and they eventually gave rise to us. Bacteria don’t get enough respect. “Bacteria may not build cities and or have interesting social lives, but they will be here when the Sun explodes. This is their planet, and we are on it only because they allow us to be.”

Bryson’s vivid, colloquial writing reflects so much more talent and hard work than its easy-going quality suggests. And it is risky: in less capable hands it could be misleading, overgeneralized, sentimental. But Bryson succeeds at a task that is crucial today when science seems too cold to appeal to many people and conventional religion seems too hide-bound for others to swallow. Bryson makes scientific information evocative, personal, the stuff of life itself. He brings us up close to the reality that the history of the universe—from the Big Bang to the building blocks of life—is around us, is in us, and is us.

He writes about lichens. “Lichens are just about the hardiest visible organisms on Earth, but among the least ambitious.” They thrive in Antarctica and other harsh climates, and they are so successful that there are 20,000 species of them. They are very slow-growing and as a result are often hundreds if not thousands of years old.

As humans we are inclined to feel that life must have a point. We have plans and aspirations and desires. We want to take constant advantage of all the intoxicating existence we’ve been endowed with. But what’s life to a lichen? Yet its impulse to exist, to be, is every bit as strong as ours—arguably even stronger…. Like virtually all living things, they will suffer hardship, endure any insult, for a moment’s additional existence. Life, in short, just wants to be.

We humans

Are inclined to feel

That life must have a

Point. We have

Plans,

Aspirations.

What’s life

To a lichen?

It’s impulse to exist,

To be,

Is every bit as strong as ours–

Arguably

Even stronger.

They will suffer

Hardship, endure

Any insult,

For a moment’s

Additional existence.

Life

Just wants to be.

The author

Brock Haussamen

I live in New Jersey and taught English at a community college for nearly four decades. I am married and have a daughter, a grandson, and step-children here in the state.

I retired from teaching in 2006 in part to move on from teaching and partly to try to help reduce poverty locally and through global advocacy. For the past few years, I’ve served as a financial coach for low-income families.

I retired from teaching in 2006 in part to move on from teaching and partly to try to help reduce poverty locally and through global advocacy. For the past few years, I’ve served as a financial coach for low-income families.

I’ve also been thinking about the questions that catch up with most of us sooner or later: What is my purpose? How will I face death? What do I believe in? I’ve always liked and trusted the descriptions from science of how living things work and how we all evolved. But I could not put those descriptions together with my questions. Gradually, I’ve been coming to see how the history of life over 3.8 billion years stands inside and throughout my being and the being of others.

In my blog at threepointeightbillionyears.com, I’ve been exploring the variety of ways in which our experience is anchored not just in our evolution from primates but in the much longer lifespan of life itself.

Naturalistic Paganism

Naturalistic Paganism

I’m definitely going to check out this book and the author’s other writings thanks to this piece, but I have to point out a formatting issue.

There are multiple quotes that appear twice in the writing, nearly back-to-back. I can’t attach a screenshot, so I’ll copy the segments of text I’m referring to:

“Incidentally, disturbance from cosmic background radiation is something we have all experienced. Tune your television to any channel it doesn’t receive, and about 1 percent of the dancing static you see is accounted for by this ancient remnant of the Big Bang. The next time you complain that there is nothing on, remember that you can always watch the birth of the universe.

Facts brought down to earth, with imagination and humor—that’s Bryson’s signature. Indulge me while I recast this passage to highlight its appeal:

TV static

Echoes of the Big Bang. Really. (howitworksdaily.com)

Tune your television to any channel

It doesn’t receive, and

About 1 percent of

The dancing static

You see

Is accounted for

By this ancient remnant

Of the Big Bang.

The next time you complain that

There is nothing

On, remember

That you can always watch

The birth of the universe.”

That’s the first one, at the beginning. The second is near the end:

“As humans we are inclined to feel that life must have a point. We have plans and aspirations and desires. We want to take constant advantage of all the intoxicating existence we’ve been endowed with. But what’s life to a lichen? Yet its impulse to exist, to be, is every bit as strong as ours—arguably even stronger…. Like virtually all living things, they will suffer hardship, endure any insult, for a moment’s additional existence. Life, in short, just wants to be.

We humans

Are inclined to feel

That life must have a

Point. We have

Plans,

Aspirations.

What’s life

To a lichen?

It’s impulse to exist,

To be,

Is every bit as strong as ours–

Arguably

Even stronger.

They will suffer

Hardship, endure

Any insult,

For a moment’s

Additional existence.

Life

Just wants to be.”

I hope this helps.

Thanks for pointing that out! In those sections, Brock is recasting the same section as if it were poetry, and that’s why he repeats it written out in short lines. He’s emphasizing the poetic nature of the text.

I understand, but from a design and readability perspective, it would look better and be more readable if the standardly formatted section of the duplicate text were removed and only the poetic sections were left.

That would make the beginning look something like this:

”

Bryson begins with the Big Bang, discovered in 1965 by scientists wondering about a hiss in the reception from a communications dish, a noise that turned out to be the cosmic background radiation left over from the Big Bang.

Facts brought down to earth, with imagination and humor—that’s Bryson’s signature. Indulge me while I recast this passage to highlight its appeal:

Tune your television to any channel

It doesn’t receive, and

About 1 percent of

The dancing static

You see

Is accounted for

By this ancient remnant

Of the Big Bang.

The next time you complain that

There is nothing

On, remember

That you can always watch

The birth of the universe.

”

I think that this current format would also be very confusing for someone using a screen reader device.

Thanks again.